As my life and career progress, I periodically question whether I have made the right decisions. Did I study the right major? Should I have taken this new job? What’s the point of hosting a website and writing articles that nobody reads? Is xyz hobby just wasting my time?

I ask questions like the ones above to evaluate efficiency. Specifically, I inquire to see if I am taking the shortest path to success (however defined).

Unfortunately, every time I have asked myself such a litany of questions, I become distressed. It seems that I always break from the straight-line path that makes sense on paper. Instead of working the corporate ladder and getting new certifications for my job, I move to a new city, change jobs, pick up a new hobby, and change my life in some other radical way. Of course, I don’t do these things unconsciously; I do them because they feel like the right choice. Nevertheless, it always seems like I am doing the least efficient thing possible to achieve that ethereal “success.”

I had started to think that maybe I was doomed to mediocrity; never being the best at something. Yes, I can do a lot of things, but I’m not the best at any one thing. I can write code, financial models, or articles, but I can’t write them as adeptly as someone who has dedicated decades to that specific field.

After a particularly existential session of questioning, I looked to the internet for some sort of vindication for my poor decision-making. That’s when I found Dave Epstein’s Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. Everything, I had heard up to this point was that you need to focus singularly on one thing, but Range challenged these ideas. The book proposed that being the best does not always lead to success and, if it does, may significantly limit its scope. At the very least, specialization is not the optimal path for everyone.

This article presents an overview of the book and some advice to those of us who are square pegs trying to fit through round holes.

Summary

Range sets a thesis: generalists are often more successful than specialists because they have diverse knowledge that helps solve “wicked problems.” Additionally, if one is to specialize, one should specialize late in their career. Society’s preoccupation with early specialization inhibits rather than promotes advancement. In practice, those who wait to specialize are better able to define their interest, and they will have developed the ancillary knowledge useful to be a successful, innovative specialist. All such things make the person more effective and motivated.

The book then goes on to prove this thesis with multiple case studies (ranging from engineering, sports, management, military, etc.). I suppose each story exhibits breadth and builds a compelling argument, but for me, the stories got repetitive (each one making the same point). The book does not win any awards from a literary perspective.

Let’s circle back to “wicked problems.” What are “wicked problems”? Novel problems that are hard to prepare for and don’t have clear answers. “Wicked learning environment” is another term you see in the book. These environments simply bring about wicked problems. The problem information does not interface well with the information of the people solving the problem (e.g., early cancer detection). Alternatively, “kind problems” and “kind learning environments” have recurring patterns and constraints that are more easily prepared for (e.g., chess and golf).

Generalists are far better at coming up with novel solutions for wicked problems. A specialist will most likely stick to the book and not consider unconventional or higher-risk approaches. This certainly can be an asset at times; for instance, the best surgeons are specialists. However, the same narrowly focused surgeon may not be the most innovative when it comes to developing new procedures.

Lessons From the Text

Development is not a linear path. In fact, the circuitous route to success is typically filled with more learning than the more direct ones. Both travelers may learn the same thing, but the one who stumbled learned extra skills. Epstein writes “it is difficult to accept that the best learning road is slow, and that doing poorly now is essential for better performance later. It is so deeply counterintuitive that it fools the learners themselves.”

Specialization lends itself to automation. While it is true that some domains are amenable to early specialization, like chess, these very narrowly defined subjects are easily automated because they adhere to strict rules. The kind learning environment of chess is the most poignant example. In 1997, IBM’s Deep Blue beat Kasparov. Overnight, the specialist’s skill that was developed over many years became trivial. This is not to belittle chess and other similar specialized pursuits, for they certainly have value in that they cultivate sharp cognition and neuroplasticity.

“Match quality” explains the fit between someone’s interests and what they do. The higher level of match quality between someone and work, the more likely someone is to excel at work. The US Army provides some insight on the topic. The Army procures officers from a few pipelines the US Military Academy (West Point), ROTC, and Officer Candidate School (OCS). West Point and ROTC offer 4-year scholarships to qualified candidates. Selected candidates are both physically and academically gifted. To receive the scholarship, you must apply during high school. Those selected are locked into a service contract with the Army after they graduate college. Notably, these high-performing recipients of scholarships have the highest attrition rate of all officers. Why is this? Well, the Army asks them to commit (specialize early) well before they can decide if the Army is truly what they want to do. Moreover, these high performers have the desire to expand their breadth beyond what the Army offers. At this point in their careers, officers have been training with the Army for at least 8 years; it only makes sense that many would not want to re-up. They rather try their hand in the civilian sector where they can make more money doing jobs with higher match quality. Epstein notes, “Three-quarters of American college graduates go on to a career unrelated to their major—a trend that includes math and science majors—after having become competent only with the tools of a single discipline.” Officers are not afforded this opportunity to switch until after their contract. If anything, many officers would leave the Army earlier if they were not bound by contract.

Other officer candidates join ROTC later in college, and many come from OCS, which matriculates students after they graduate college. These groups of officer candidates are older and have a much higher retention rate after serving their first contract. These individuals have had time to study different things, do different jobs, and have more life experience. This larger “sampling period” improves match quality. Their tendency to stay in longer is consistent with Epstein’s explanation: “The more confident a learner is of their wrong answer, the better the information sticks when they subsequently learn the right answer. Tolerating big mistakes can create the best learning opportunities.”

The Army has many specialties (or branches) within it. Officers can become infantrymen, aviators, engineers, etc. In the past, cadets were given some level of preference for their branch, but they had no direct experience with the jobs themselves. Many would get assigned and not enjoy their jobs. At first, the Army decided that these cadets were not gritty enough, so the Army tried to improve selection to find individuals with grit. It soon became apparent that match quality was the solution not grit. Match quality looks like grit when done right. Think of “Grit as a state, not a trait.” To improve retention again, the Army introduced a program that allowed cadets to shadow officers from each branch. This extended the sampling period and improved the match quality for officers and their respective branches.

Generalists Excel at Fermi problems. The physicist Enrico Fermi is famous for estimating the power of an atomic bomb based on how far pieces of paper went when he dropped them during the blast. Fermi problems, which are often used as interview questions, are estimation problems. You have very little data to solve these problems and must rely on sound reasoning and background knowledge to answer them. Interviewers do not expect the right answers, but they look to see that the interviewee can come up with a reasonable procedure and make connections to solve these wicked problems. Questions such as how many tennis balls fit into an airliner? Or, my favorite one at the time of writing, what are the chances that two people in London have the same number of hairs on their heads? I encourage you to watch this Numberphile video to learn more.

Numberphile video on Fermi Problems

My Experience With Specialization and Generalization

I find Epstein’s message appealing. It justifies my choices and path. I bounce around to different fields and hobbies with haste. I’ve tried to specialize in the past, but I fall into burdensome restlessness. To stay engaged, I need work that requires multi-faceted intelligence. Such a constraint leads me to change jobs frequently. Is this a cop-out? Am I just lazy? In the past, I thought so. However, I currently believe it is simply my design.

My breadth of knowledge comes in handy often. In quant-heavy roles like programming, I can offer new ideas that come from more qualitative experiences. The opposite applies when working in qualitative roles such as sales. On a personal level, my breadth of knowledge allows me to better connect with people. I usually am well versed enough in others’ fields or interests to have a quality discussion. Just the other day at a conference, I befriended a gentleman from Angola simply because I had a cursory understanding of his country’s history and politics. Diverse, even random, knowledge unexpectedly helps with dating too. I’ve swooned more than a few liberal arts students by having a rudimentary understanding of their favorite philosopher.

Epstein’s position that early specialization causes inefficiency also rings true with me. In my youth, I overspecialized in athletics, developing overuse injuries that I would carry with me into adulthood. I would have been better served by taking the Roger Federer approach: play multiple sports until reaching a more mature age and commit with greater rigor and intelect. Such an approach would have likely resulted in better health and competitive success.

I also overspecialized in academics. Academic specialization was first instilled in me when I was in middle school. My middle school was full of bright pupils who intended to attend selective high schools. All these schools had admissions exams, so the middle school offered classes to help students prepare. Of course, to attend these courses I had to forego doing things that I enjoyed. Anyway, the idea was that attending an elite high school would lead to attending an elite university which would lead to a high-paying first job and a successful career. Truth be told, this correlation exists but only for kind learning environments.

Academic specialization would only increase at each level of education. I had to further specialize in standardized tests during high school and demonstrate to universities a commitment to a specific field (economics, English, programming, math, etc.). Of course, at university, I further specialized in the subject matter. Upon graduating university, I had spent 8 years focusing on my supposed field of interest. This singular focus for the most part backfired. I started to loathe the subject matter just as I was finally entering the professional workforce. Pity. I would have been far more engaged in my learning had I taken a liberal arts approach to education. School for me was never about learning material. It was only about passing exams. Predictably, it turns out that many of the complex skills that I learned in university have been of little use in my professional career. I focused all this energy just to prove I was intelligent, but I never took the time to internalize anything I learned.

Advice for Generalists

To reiterate, this advice is directed toward people like me. Someone who has done many things, has many interests, yet has never committed to a singular, strict path. How can we move towards success with grace, and avoid bouts of self-conscious, existential questioning? Here are some ideas that resonate with me:

1) Cultivate varied skills and apply them dynamically.

- Doing so makes you unique and valuable. Similar to combinatorics; the number of combinations grows strikingly as the number of elements in the set increase. In other words, the more varied your knowledge, the more likely you are to offer a perspective that no one else has, making you more capable than a narrowly focused person.

2) The best process for short-term results does not often lead to the best long-term results.

3) “We learn who we are in practice, not in theory.”

- If you don’t try many things, how will you know what you enjoy or resonate with? The best musicians often settle on their third or fourth instrument.

4) Adjust time preference, so you can better match your work preference.

- Don’t focus on the carefully plotted retirement plan. Doing so locks you into work that you may not like in the future. “Our work preferences and our life preferences do not stay the same, because we do not stay the same.” Your favorite artist as a teenager is probably not your favorite artist now. Instead, focus on the short term. What motivates you now? Pursue that. You’ll be happier in the long run.

5) Open doors. Don’t close them.

- “I propose instead that you don’t commit to anything in the future, but just look at the options available now, and choose those that will give you the most promising range of options afterward.”

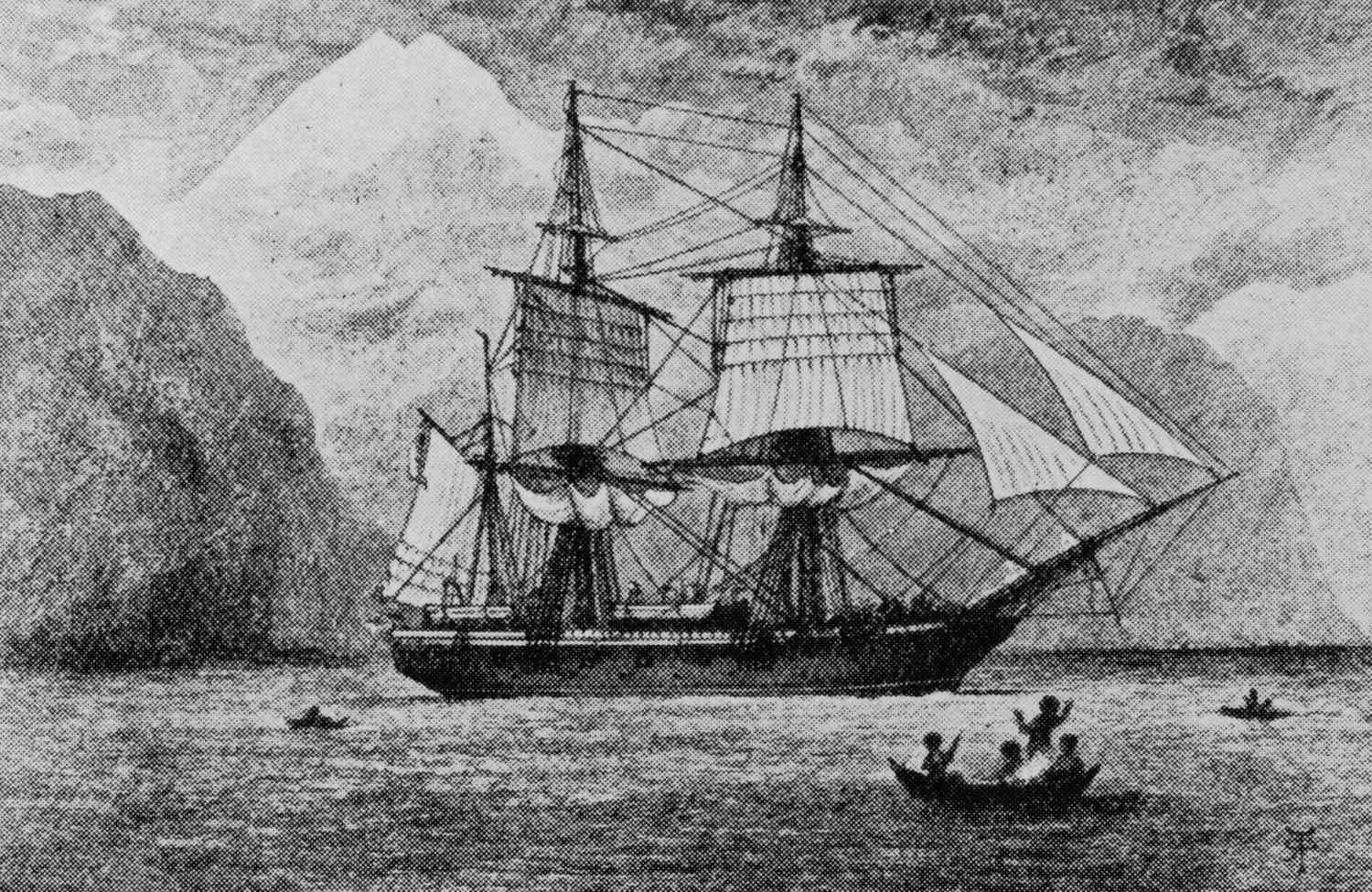

6) Don't fall victim to the sunk cost fallacy.

- Victims of the fallacy make decisions based on what they did before rather than what may be most beneficial at present. Don’t fall victim. Before Darwin got aboard the HMS Beagle and sailed to the Galapagos, he had trained not only in natural history but also medicine, theology, philosophy, and geology.